Propagating uncertainty from inputs to outputs of a function

Assume we have a scalar function of several inputs \(f(x_1,x_2,\dots)\). In this note I'll look at different ways to quantify how randomness or uncertainty in the input variables \(x_1, x_2, ...\) translates into randomness or uncertainty in the function value.

Exact methods

Univariate functions

Let's first consider univariate functions, i.e. \(y=f(x)\), where \(f\) is a known function. For a random variable \(X\) with a known distribution, applying a transformation \(f(X)\) results in a new random variable \(Y\) whose distribution and statistical properties (such as expectation and variance) can (sometimes) be derived from those of \(X\).

Transformation of Expectation: Expectation is not a measure of uncertainty, but is important enough for us to include here anyway. \(E[Y]\) can be calculated directly when the transformation is linear \(f(x) = ax + b\): $$E[Y] = E[aX + b)] = aE[X] + b = f(E[X]).$$

When the transformation \(f\) is non-linear, we can sometimes use the Law of the Unconscious Statistician (LOTUS) to calculate the expectation of \(Y=f(X)\). When \(p(x)\) is the pdf of \(X\) we have $$E[Y] = E[f(X)] = \int f(x) p(x) dx$$ where the integral is over the domain of \(X\). However, integrating \(f(x)p(x)\) analytically might not be possible.

Transformation of Variance: \(Var[Y]\) can be calculated directly for linear transformations \(f(x) = ax + b\): $$Var[Y] = Var[aX + b] = a^2 Var[X].$$

When \(f\) is nonlinear but not too "complicated", we can use the LOTUS to also calculate the variance of \(Y\): $$\begin{aligned}Var[Y] & = E[Y^2] - E[Y]^2 = E[f(X)^2] - E[f(X)]^2\\ & = \int f(x)^2 p(x) dx - \left[ \int f(x) p(x) dx \right]^2.\end{aligned}$$ As before, depending on the transformation and pdf the integrals might not be tractable.

Transformation of the Whole Distribution: The whole pdf of \(Y\) can be derived from the distribution of \(X\) using the change of variables technique. For simplicity we will assume here that \(f(x)\) is monotonic (either strictly increasing or strictly decreasing), and differentiable over the range of \(X\). We assume that the inverse transformation \(x = f^{-1}(y)\) is known. The pdf of \(Y\), denoted \(q(y)\) is then given by $$q(y) = \left| \frac{d}{dy}f^{-1}(y)\right| p(f^{-1}(y))$$

Multivariate functions

When the transformation \(f\) is multivariate, this means that the transformed random variable \(Y\) depends on several random variables \(X_1, X_2, \dots\). We merge them into a random vector \(X = (X_1, X_2, \dots)^T\) which has an expectation vector \(\mu = (\mu_1, \mu_2, \dots)^T\), a variance-covariance matrix \(\Sigma\) has elements \(\Sigma_{ij} = Cov[X_i, X_j]\), and joint pdf \(p(X) = p(X_1, X_2, \dots)\).

When the transformation \(Y=f(X)\) is linear we have \(f(X) = AX + b\) where \(A\) is a matrix with one row and b is a scalar. The expectation of \(Y\) is then given by \[E[Y] = A\mu + b\] and its variance is given by \[Var[Y] = A\Sigma A^T\]. The pdf \(q(y)\) of \(Y\) can be derived from \(p(x)\) by the change of variable formula \[q(y) = \int_{\mathbb{R}^n}p(x)\delta(y - f(x))dx.\] More background can be found on wikipedia. But I have not seen change of variable being used much for uncertainty propagation so won't go into detail right now.

Delta method

Delta method: The Delta Method is used to approximate the variance of a transformed random variable \(Y = f(X)\). It is particularly useful when dealing with non-linear differentiable transformations \(f(x)\). To apply the Delta Method, the expectation \(\mu\) and variance \(\sigma^2\) of the untransformed variable \(X\) must be known. We first Taylor-expand \(f(X)\) around \(\mu\): \(Y = f(X) \approx f(\mu) + f'(\mu) (X - \mu)\) where \(f'(\mu)\) denotes the derivative of \(f\) evaluated at \(\mu\). Under this approximation, the expectation of \(Y\) is \(f(\mu)\). The Taylor approximation of \(Y\) is a linear function of \(X\) so the approximate variance of \(Y\) is given by \[Var[Y] \approx [f'(\mu)]^2 \sigma^2.\]

The Delta method is also applicable to multivariate functions \(Y=f(X_1, X_2, \dots)\). Let \(\nabla f(x)\) denote the gradient of \(f\) evaluated at the vector \(x=(x_1,x_2,\dots)^T\). Then the variance of \(Y = f(X)\) is approximated by $$Var[Y] \approx \nabla f(\mu)^T \Sigma \nabla f(\mu).$$

Monte Carlo simulation

The foundation for Monte Carlo methods is the Law of Large Numbers, which states that as the number of trials in a random experiment increases, the average of the results from all trials converges to the expected value. This principle underpins the reliability of Monte Carlo simulations for uncertainty propagation: By simulating a system many times with randomly sampled input parameters, we can approximate the distribution of the output, including its variance and other statistical properties.

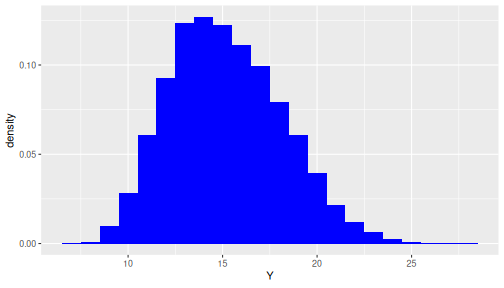

Monte Carlo methods involve generating a large number of realisations of input variables sampled from their respective distributions. Then we calculate the output of the transformation for each sample of input variables. The collection of outputs then provides a statistical sample of possible outcomes. From this we can derive the empirical distribution, as well as expectation, variance, etc of the output variable. The Monte-Carlo approach is particularly valuable for non-linear transformations, transformations that are not given in mathematical closed form.

Below is an R code chunk that demonstrates a Monte Carlo simulation where \(X_1\) is initial velocity and \(X_2\) is initial angle of a projectile fired from ground level. The output \(Y\) is the maximum height of the projectile, given by \[Y = f(X_1, X_2) = \frac{X_1^2 \sin^2(X_2 \pi / 180)}{2g}\] where \(g = 9.81\) is the gravitational acceleration. If we are uncertain about \(X_1\) and \(X_2\), we are also uncertainty about \(Y\). We will describe our uncertainty in the velocity \(X_1\) by a Normal distribution, and uncertainty in the angle \(X_2\) by a Uniform distribution.

# simulate random inputs

X1 = rnorm(1e4, mean = 30, sd = 2) # Initial velocity (m/s)

X2 = runif(1e4, min = 30, max = 40) # Projection angle (degrees)

# calculate output

Y = (X1^2 * sin(X2*pi/180)^2) / (2 * 9.81)

# Plot the density histogram of the output

ggplot() + geom_histogram(aes(x=Y, y=after_stat(density)),

binwidth = 1, fill = "blue")

print(c(`mean(Y)` = mean(Y), `var(Y)`=var(Y), `sd(Y)`=sd(Y)))

## mean(Y) var(Y) sd(Y)

## 15.195385 8.819005 2.969681

f = ~x1^2*sin(x2*pi/180)^2/(2*9.81)

deriv_f = deriv(f, c('x1','x2'), function(x1,x2){})

grad_f = function(x1, x2)

as.vector(attributes(deriv_f(x1, x2))$gradient)

grad_f_mu = grad_f(30, 35)

Sigma = diag(c(4,100/12))

drop(t(grad_f_mu) %*% Sigma %*% grad_f_mu)

Next steps

As next steps in studying uncertainty propagation, here are some questions we might ask to move forward:

- Sometimes the distributions of input variables aren't clearly defined. How should expectations, variances or distributions of input variables be specified when we have no or only imprecise knowledge about their uncertainty?

→ Expert elicitation

- Calculation of the output might be computationally expensive, so generating 1000 Monte Carlo samples is not possible. What should we do?

→ Surrogate modelling

- How can we quantify how much each of the inputs affects uncertainty in the output? Is the output more sensitive to some inputs than to others?

→ Sensitivity analysis

- Can we explore the space of input variables more efficiently than by sampling randomly and independently?

→ Design of Experiments